Nauta’s non-fragile strategy: Investing in companies with Maximum Sustainable Growth

Nassim Taleb’s concept of fragility applies to VC investment

The primary goal of fund managers (the GPs) should be to achieve maximum risk-adjusted returns for the investors in their funds (the LPs). To achieve this over the long term, we at Nauta employ an investment strategy that we believe is 'non-fragile' in Nassim Taleb’s sense, i.e., it should succeed through all macro environments and economic cycles and should avoid being “fooled by randomness”.

Preventing fragility is critical in VC given that the median fund lifespan has, over many vintages, exceeded the ten years typically agreed in VC fund articles: the average lifespan as of 2023 was 13 years according to Pitchbook, with 70% of funds at that time older than 10 years, while the Institutional Investor already reported an average lifespan of 14 years in 2015.

GPs cannot know which macro environment their funds are going to face through the phases of investing, growing and exiting but, given the median lifespan of a VC fund, they should be aware that those environments will be varied. For instance, below you can see the very different circumstances our last three funds were met with: a phase that may have been favourable for one fund was potentially unfavourable for another.

Following a fragile strategy in VC (as a result of conscious choice, lack of discipline, investments based on momentum only or a shallow level of analysis) may have succeeded with a 2014-vintage fund. Those funds were lucky to have an investment period coinciding with depressed valuations and enjoyed a bull run through the exit period. However, such a fragile strategy would have been disastrous with a 2019 fund, which faced inflated valuations during the investing period and a bear market in its growing years (2022-2025).

By following a non-fragile strategy, every Nauta fund has the same chance to achieve market-leading returns regardless of the VC environment. Otherwise, we expose our funds and portfolio companies to the randomness and turbulence of macroeconomics.

Maximising Enterprise Value at exit is a fragile strategy and doesn’t align the main stakeholders in VC

In many influential VC circles, the investment strategy is to “go big or go home”, where the main metric to maximise is the portfolio companies’ EV at exit. This strategy has been proven to lead to outlier fund returns in the good times since the failures in the portfolio amount to a rounding error next to the monumental returns from the winner(s).

We understand that VC is a game with a Power Law distribution of outcomes. Our point is that the “go big or go home” strategy is fragile and, therefore, leaves LPs exposed to the randomness of the environment. Besides, such approach generates a principal-agent problem since the GPs profit handsomely from a successful fund outcome but do not suffer the fund losses. This has led to excessive risk-taking across the VC industry and has resulted in major losses for LPs in many funds.

This EV-maximisation strategy overlooks another key stakeholder in the VC world: the entrepreneurs. GPs following the “go big or go home” strategy are incentivised to encourage founders to take outsized risks and push for unsustainable growth. However, founders are risking their life’s work and the outcome of their own company is all they will get, whereas the GPs have many options in their portfolio.

We believe that there is another way to do venture capital which better aligns all the stakeholders.

A non-fragile strategy optimises for Expected Enterprise Value at Exit (EEVE)

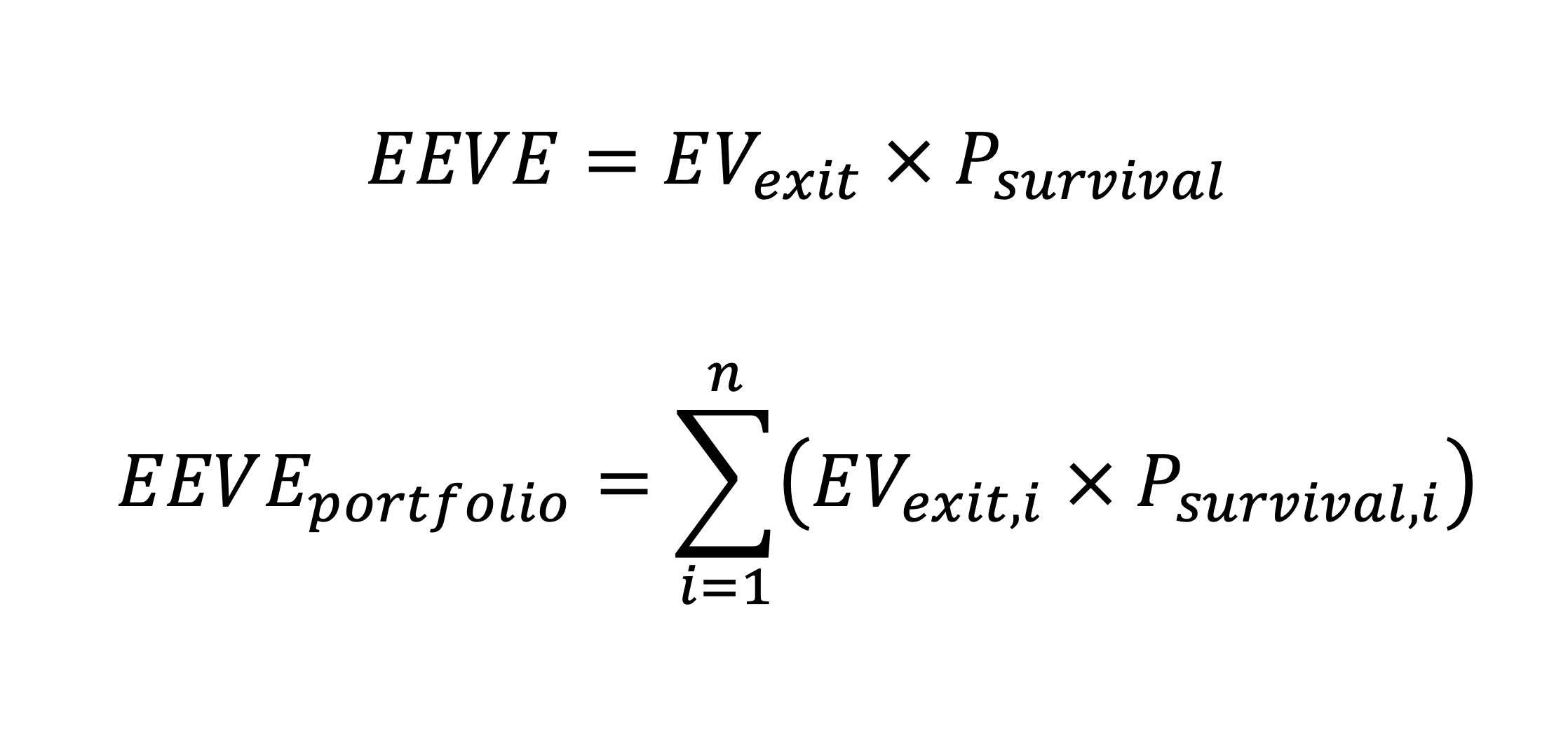

A GP must maximise their risk-adjusted returns, which are highly correlated with the net present value of the cashflows arising from a fund’s investments. For a VC fund, since portfolio companies don’t pay dividends, the cash inflows are solely the proceeds from divesting companies with positive Equity Value, i.e., with Enterprise Value (EV) above net debt. We call the probability of this accretive exit happening as the probability of survival of the portfolio company.

For optimal risk-adjusted returns, a non-fragile strategy should maximise the Expected Enterprise Value at Exit (EEVE) of portfolio companies, with EEVE defined as the product of the Enterprise Value at exit and the probability of survival.

In contrast, a fragile strategy aims at maximising portfolio companies’ Enterprise Value at exit but doesn’t take into account the probability of survival, hence exposing funds to brutal losses of net asset value.

How is the EEVE maximised?

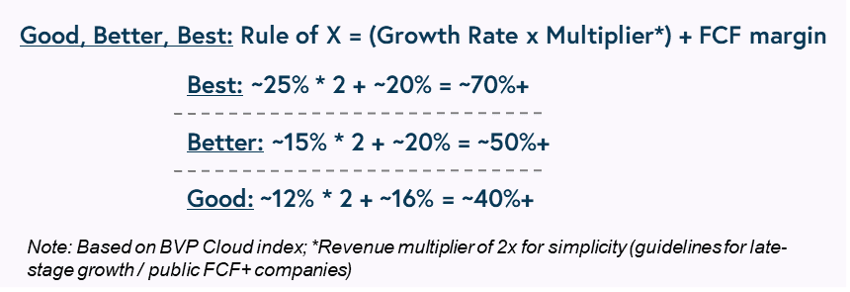

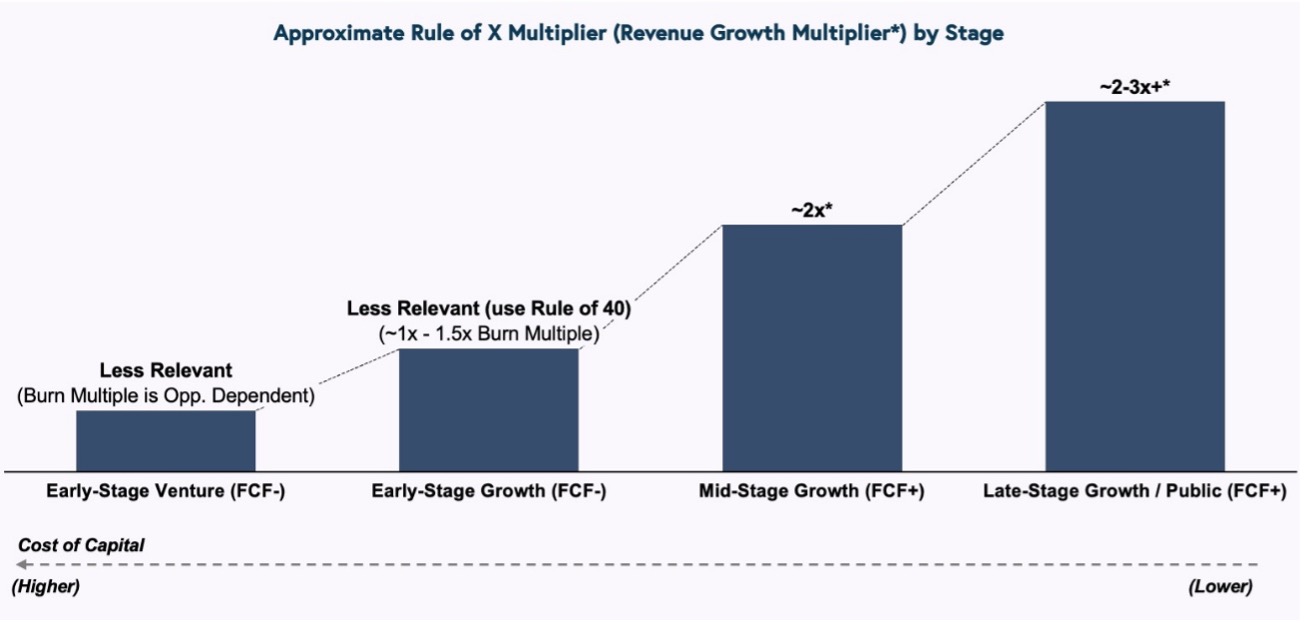

As per Bessemer’s Rule of X, the Enterprise Value (EV) of cloud businesses can be regressed to a linear function of revenue growth and free cash flow (FCF) generation where the revenue growth has a higher coefficient (i.e., a 1% increase in revenue growth increases EV more than a 1% increase in free cash flow).

As per said rule, to increase a company’s EV, you need its revenue growth to be higher. However, to improve its probability of survival, you need its cash flow to be sustainable. Therefore, a maximum rate of revenue growth that is sustainable in terms of cash flow optimises for EEVE.

If we assume that revenue growth and FCF are inversely correlated, then, to optimise for EEVE, the company should aim at maximising the revenue growth while maintaining the minimum FCF that is sufficient to sustain the company until an exit that turns the EV into cash returns for the investors.

Having long terms sustainable revenue growth is not only necessary for a company to avoid reducing its probability of survival excessively. It is also necessary to maximise the EV at exit because, since the time of exit cannot be known in advance, the company should maintain the maximum possible revenue growth throughout its life, as the realised EV directly correlates with it.

For a company to achieve maximum EV, the duration of the revenue growth is as key, if not more, than the level of growth. Historic experience proves that what builds the largest companies is not short bursts of high revenue growth but sustained growth over the long term.

Companies should manage cashflow sensibly to increase the probability of survival

In our portfolio, we seek large outcomes to generate the promised returns for our LPs; and hence we encourage our companies to develop and grow as fast as possible. But we also understand that early-stage companies need to survive until they solve the challenges of their actual stage of development if they are to progress to the next stage of development and attract new funding.

During the very early stages of development (i.e., during the discovery of the job-to-be-done, the customer, and the market), we recommend our portfolio companies be cautious with their capital. We’ve seen too many companies jumping ahead of their true development phase and burning too much too early: a phenomenon named “premature scaling due to inconsistency” by the memorable Startup Genome reports on Why Startups Succeed and Why Startups Fail. This is a recipe to blow up down the line.

Only when the questions of their current stage are properly answered, do we encourage our companies to accelerate to the next level and have a shot at becoming global leaders. For instance, Cledara could prove product-market fit quickly after our investment in 2020 and, since it engineered a short sales cycle and revenues grew quickly, the company sped to a new round within a few months.

If a company is taking longer than budgeted to solve the challenges of their current development phase, there are two ways to extend the cash runway:

- Expenses are cut drastically to decrease cash burn; and

- Existing shareholders bridge its cash needs until break-even.

Option one reduces the likelihood of the company solving those challenges, thereby stunting the development and limiting the attractiveness for new investors. Sometimes, however, cost-cutting is the right medicine, and we have seen several bloated companies performing much better after this.

Option two theoretically preserves the chances of reaching the next stage but clearly this involves a difficult discussion between existing shareholders where their real conviction in the company’s eventual success may be tested. In any case, the extra runway that the existing shareholders can provide is usually no longer than 12 months, unless an external party is convinced to join the bridge (but this is uncertain and, therefore, relying on this event is a fragile strategy).

Introducing Maximum Sustainable Growth to optimise EEVE

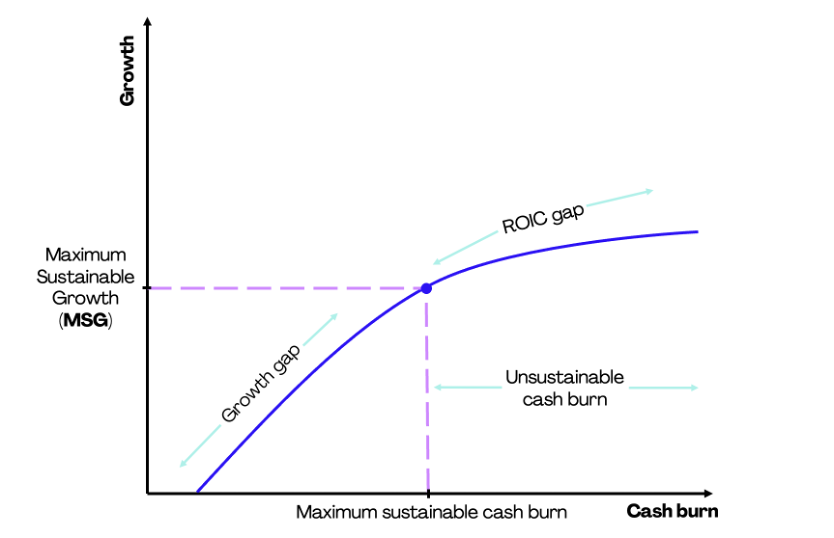

Here we introduce a key concept: the Maximum Sustainable Growth (MSG), which we define as the growth provided by the highest rate of cash burn that enables the required development to attract new investors, whilst simultaneously allowing the company to reach net cash breakeven. All within a cash runway that can be supported by the current shareholders.

A company with growth lower than MSG has a “growth gap”, i.e., it is growing less than the potential at its most efficient state (akin to an output gap in the economy). This leads the company to be out of trouble, growing slow and steady, but does not make it attractive to new investors.

A company with growth higher than MSG has a “ROIC gap”, i.e., it is achieving less than its potential Return on Invested Capital at its most efficient state. This leads the company to grow revenues quickly but wasting capital and not maximising the EVEE.

A company at MSG is growing and burning cash at the right pace to attract new investors whilst keeping its destiny in its own hands. If delayed in their development, a company at MSG could extend its cash runway with the support of their existing shareholders without having to resort to a drastic cost reduction that may irreparably damage its future. Merely keeping the expenses at the existing level should be sufficient to survive until new investors are convinced.

An MSG strategy enables the company to maximise enterprise value potential while protecting the enterprise value created. It also allows for a longer duration of revenue growth, which results in more durable growth of the enterprise value. MSG also reduces the overall dilution of the cap table and increases the enterprise value captured by the company’s founders and early investors.

How to calculate the MSG?

To achieve the MSG, our typical advice for early-stage, revenue-generating companies is that their revenue growth and cash burn trajectory should enable them to reach net cash breakeven within six months of the end of runway, without drastically cutting expenses and accounting for high certainty revenue growth only.

Obviously, it’d be better if the breakeven was achieved before running out of cash, but if the company has good prospects to raise another round or exit, the existing shareholders might be able to bridge the extra months of runway required. Discussions around bridge rounds should happen about 12 months before the zero-cash time for the company to be able to budget appropriately. It’s worth noting that a company is unlikely to be able to get bridged twice, and, if so, the second bridge will most probably go through drastic cost cutting.

For mid- and later-stage companies, our usual advice on how to calculate the MSG is aligned with the Bessemer’s Rule of X:

- Piece of advice #1: "Make sure you control your destiny...", for example, your last-three-months net cash burn should be equal or slightly greater than zero, or your FCF should cover debt repayment, interest, and taxes.

- Piece of advice #2: "...and any FCF surplus should be reinvested in growth that does not deteriorate the unit economics and CAC payback too much".

From experience, a good scenario in terms of capital efficiency is for the company to exceed annual revenues of €5M by using less than €10M in funding; and as it grows towards €100M annual revenues, their cash burn multiple should decrease towards 1x and below.

Our investment strategy strives to be resilient and not fragile

In summary, we at Nauta follow a resilient, non-fragile investment thesis: We aim at maximising the Expected Enterprise Value at Exit of our portfolio companies. For that, we invest in great potential, capital-efficient companies that always strive for the Maximum Sustainable Growth.

We analyse sectors, companies, and business models in detail and with patience to understand the probability of outsized success and the probability of survival. Then we work tirelessly to improve both probabilities in our portfolio companies.

In VC, surviving is winning. To survive the inescapable Power Law in the long term, VC investors must focus on both the probability of outsized success and the probability of survival of their portfolio companies. This strategy better aligns all the main stakeholders in venture capital: GPs, LPs, founders, and employees. We encourage our team and portfolio to adhere to the more economically sustainable model we believe venture capital should be.

If you're building software that aims at transforming industries or markets and you're thinking about how to maximise your growth in a sustainable manner, we want to hear from you.